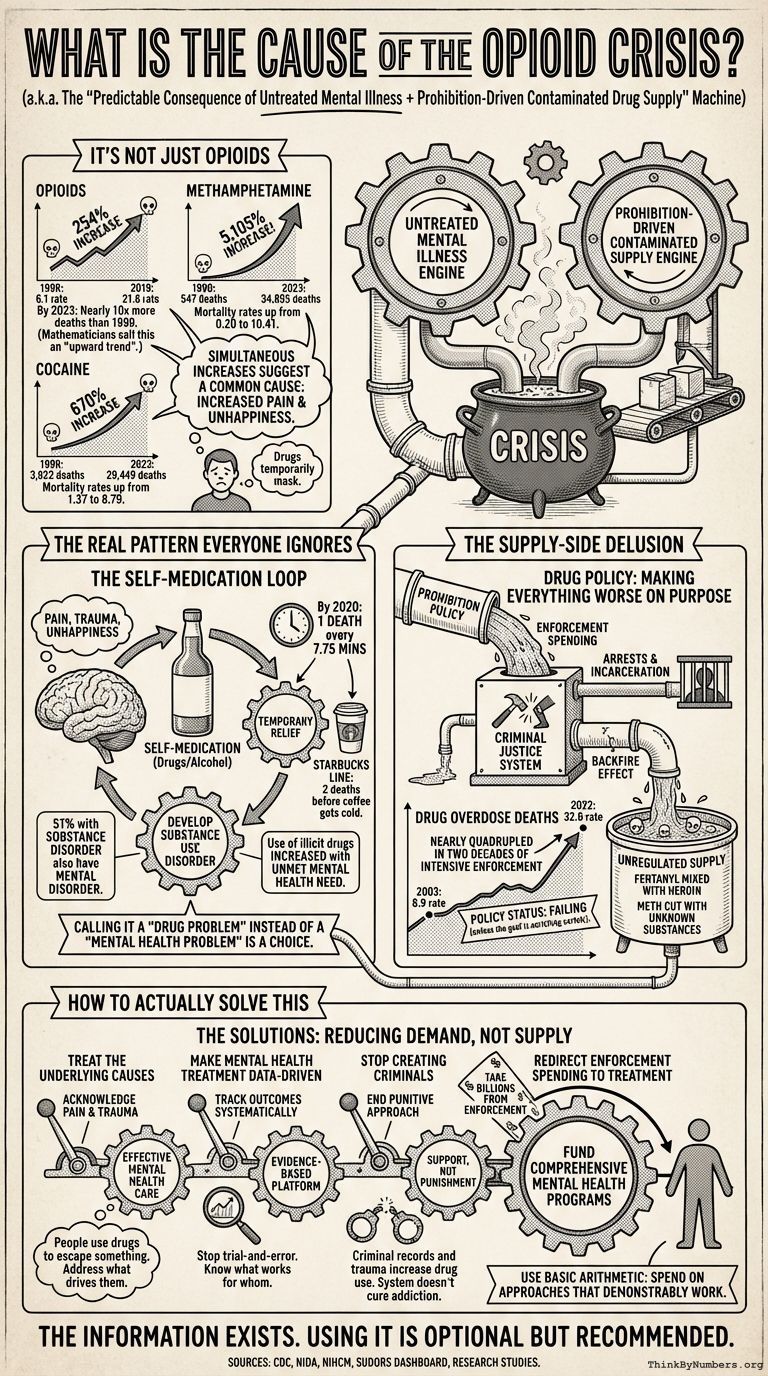

The opioid crisis is called a "crisis" because calling it "a predictable consequence of untreated mental illness combined with prohibition-driven contaminated drug supply" doesn't fit in headlines.

It's Not Just Opioids

The recent explosion in drug deaths affects multiple substance categories. The data is quite clear about this, assuming one can read charts:

Opioid Deaths: The age-adjusted rate increased from 6.1 per 100,000 in 1999 to 21.6 in 2019—a 254% increase. By 2023, nearly 10 times more people were dying from opioid overdoses than in 1999. That's what mathematicians call "an upward trend."

Methamphetamine Deaths: Rose from 547 deaths in 1999 to 34,855 in 2023, with mortality rates climbing from 0.20 to 10.41 per 100,000—a 5,105% increase. The age-adjusted rate increased from 0.2 in 1999 to 7.5 in 2020, with different rates of change over time.

Cocaine Deaths: Increased from 3,822 to 29,449, with mortality rates rising from 1.37 to 8.79 per 100,000—a 670% increase. The age-adjusted rate went from 1.4 per 100,000 in 1999 to 6.0 in 2020.

When deaths from opioids, cocaine, and methamphetamines all increase simultaneously by hundreds or thousands of percent, this suggests a common underlying cause. That cause is not "drugs suddenly became more addictive." Drugs didn't change. The people using them did.

Or more precisely, what happened to the people using them changed.

The Real Pattern Everyone Ignores

The increase in self-medication using multiple types of mind-altering drugs suggests an overall increase in pain and unhappiness, which these drugs temporarily mask. People don't suddenly decide to destroy their lives with drugs because drugs became more available. They do it because something is profoundly wrong in their lives.

By 2020, one person was dying of an opioid overdose every 7.75 minutes. That's a person dying while you're waiting in line at Starbucks. Then another one dies before your coffee gets cold.

In the National Comorbidity Study, 51% of those who met criteria for a substance disorder also met criteria for a mental disorder. Approximately 20% of people with an alcohol or drug use disorder have a co-occurring mood disorder. When half of people with drug problems also have mental health problems, calling this a "drug problem" instead of a "mental health problem" is a choice.

Research shows that individuals who self-medicate mood and anxiety symptoms with drugs are significantly more likely to develop substance use disorders. Use of illicit drugs increased with unmet need for mental health care (4.4% versus 3.2%). When you don't treat the underlying condition, people find their own treatment. The treatment they find kills them.

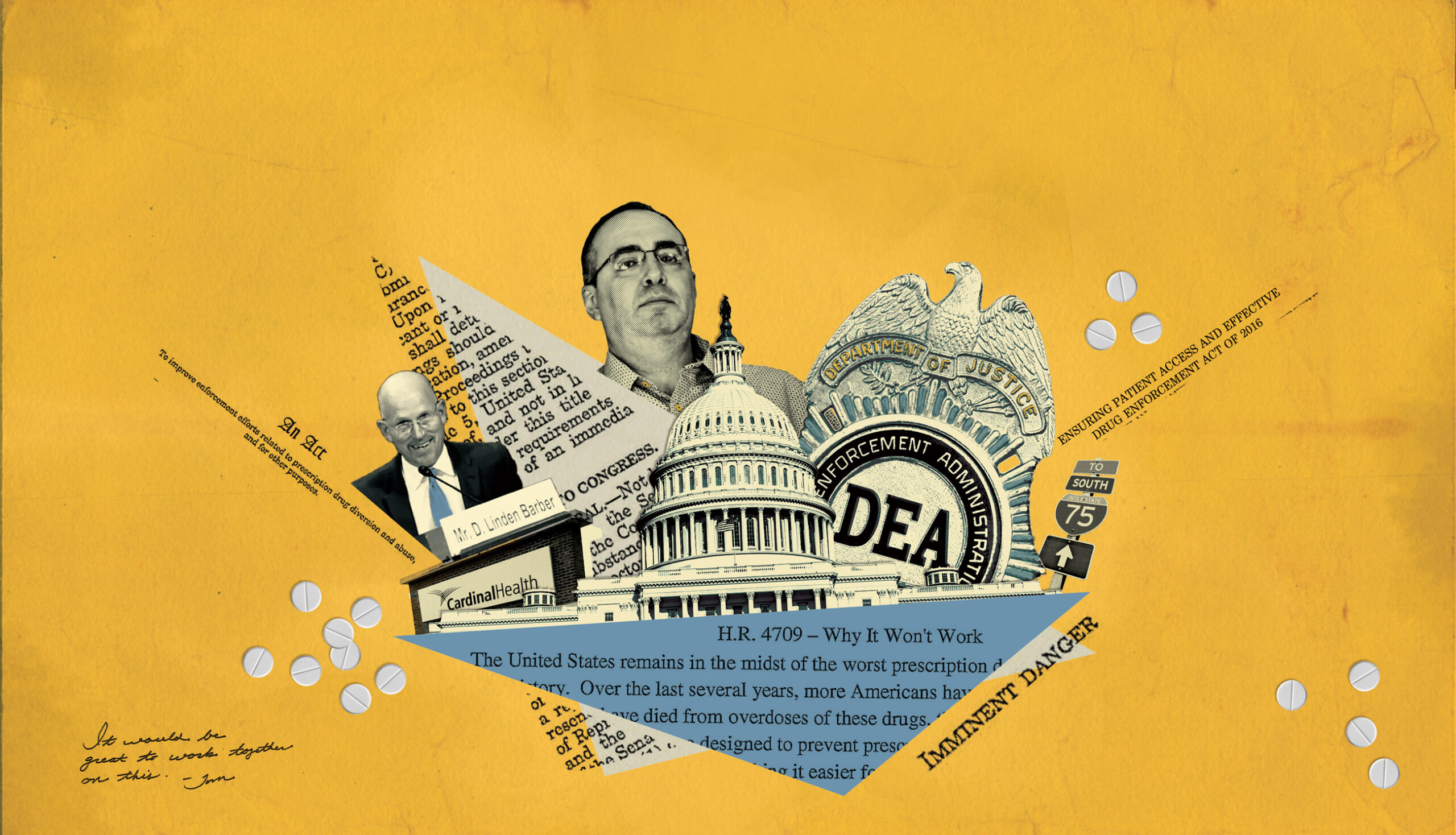

The Supply-Side Delusion

The government's response to people self-medicating mental illness has been to make the drugs more dangerous and the people using them into criminals. This is called "drug policy" but could more accurately be called "making everything worse on purpose."

When prohibition makes drugs illegal, they're manufactured in unregulated environments. Fentanyl gets mixed with heroin. Methamphetamine gets cut with unknown substances. People die not from the drug they chose to take, but from the contaminants in the drug they didn't know they were taking.

The data on prohibition's effectiveness is unambiguous: Drug overdose deaths increased from 8.9 per 100,000 in 2003 to 32.6 in 2022, then decreased slightly to 31.3 in 2023. That's nearly a quadrupling of the death rate in two decades of intensive drug enforcement.

If the goal was to reduce drug deaths, this policy is failing. If the goal was to increase drug deaths while enriching cartels and expanding the prison system, this policy is working perfectly.

How to Actually Solve This

Any solution must focus on reducing demand, not supply. Alcohol prohibition and marijuana prohibition demonstrated that supply-side enforcement is ineffective and causes more harm than it prevents. This requires observing reality and adjusting accordingly, which is why it will never happen.

Here's what would actually work:

1. Treat the Underlying Causes

People use drugs to escape something. That something is usually untreated mental illness, trauma, or unbearable life circumstances. Addressing what drives people to drugs requires acknowledging that humans use substances to cope with pain—physical, emotional, psychological.

The self-medication hypothesis is well-established in research: people with mental health conditions use drugs to manage symptoms that aren't being adequately treated by the mental health system. When the legitimate medical system fails to provide relief, people turn to the illegitimate drug market.

2. Make Mental Health Treatment Data-Driven

The current approach to mental health care operates without systematic outcome tracking. It's like treating infections without knowing which antibiotic works for which bacteria. With 0.1% of the money spent on drug enforcement, a data-driven mental health platform could track what treatments actually help which patients, reducing the trial-and-error approach that leaves people suffering for years.

When people can't access effective mental health treatment, they access effective self-medication. The difference is that one is regulated and safe, while the other is unregulated and lethal.

3. Stop Creating Criminals

Arresting people for drug possession adds criminal records, incarceration trauma, and barriers to employment on top of whatever drove them to drugs in the first place. This is like treating a broken leg by hitting it with a hammer while lecturing the patient about calcium intake.

The criminal justice system does not cure addiction. It doesn't cure mental illness. It doesn't reduce drug use. What it does do is ensure that people with substance use disorders also have criminal records, housing instability, and difficulty finding employment—all of which increase the likelihood of continued drug use.

4. Redirect Enforcement Spending to Treatment

The billions spent on interdiction, arrests, and incarceration could fund comprehensive, evidence-based mental health programs. This requires basic arithmetic to understand: taking money currently spent on a policy that demonstrably doesn't work (enforcement) and redirecting it to approaches that demonstrably do work (treatment).

The CDC's provisional data shows overdose deaths continuing despite decades of enforcement spending. The SUDORS Dashboard provides detailed fatal overdose data across states. All of it shows the same thing: enforcement isn't working.

The Inconvenient Truth

The data clearly shows what doesn't work: supply-side enforcement. The data also shows what does work: addressing demand through treatment and reducing the underlying causes of suffering.

But addressing demand requires admitting that many Americans are in enough psychological pain that death via fentanyl-laced drugs seems preferable to continuing to live with that pain. It requires acknowledging that the mental health system is failing millions of people. It requires fundamentally rethinking how society addresses mental illness, trauma, and despair.

Supply-side enforcement requires none of that. It just requires arresting people and requesting larger budgets.

Since 2000, there has been a more than 1,000% increase in opioid overdose deaths. In 2023, 105,007 drug overdose deaths occurred. Each of those deaths represents a person who needed help and got handcuffs instead. Or got nothing at all.

The information needed to solve this crisis exists. Using it is optional but recommended.

Sources

- CDC: Understanding the Opioid Overdose Epidemic

- CDC: Drug Overdose Deaths in the United States, 1999–2019

- NIDA: Drug Overdose Deaths: Facts and Figures

- CDC: Provisional Drug Overdose Data

- CDC: Drug Overdose Deaths in the United States, 2003–2023

- Methamphetamine and Cocaine Overdose Deaths in the United States, 1999–2023

- NIHCM: Visualizing the Impact of the Opioid Overdose Crisis

- Self-Medication of Mental Health Problems: New Evidence from a National Survey

- A Longitudinal Investigation of the Role of Self-Medication in the Development of Comorbid Mood and Drug Use Disorders

- Self‐medication with alcohol or drugs for mood and anxiety disorders: A narrative review

- CDC SUDORS Dashboard: Fatal Drug Overdose Data

Comments