The FDA's Mandate is Not to Maximize Lives Saved

The FDA is called that because it's an acronym, which is when you take the first letters of several words and make them into a shorter word. FDA stands for "Food and Drug Administration." They administer food and drugs. Administering is what you call it when you're in charge of something but you're not exactly sure what you're doing with it.

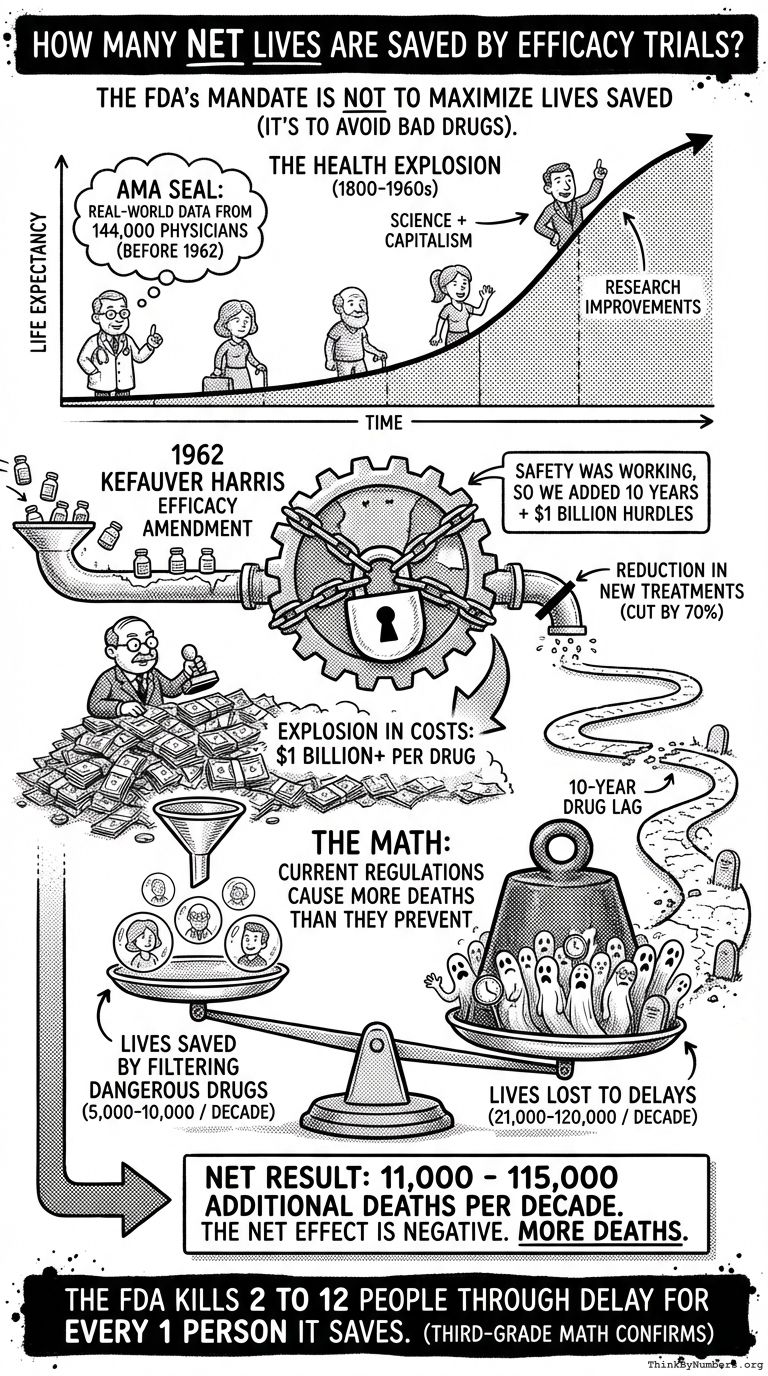

The FDA's job is to ensure "safety and efficacy of drugs and medical devices." Not to save the most lives. Not to reduce disease. Not to increase longevity. Just to make sure unsafe drugs don't get approved. The mandate is very specific. Stay in your lane. Your lane is "preventing bad things" not "enabling good things."

This is like hiring a lifeguard whose only job is to make sure no one drowns using an unsafe life preserver. People can drown without a life preserver all day long. That's not the lifeguard's problem. The lifeguard's job description says "life preserver safety inspector" not "prevent drowning." Reading comprehension is important in bureaucracy.

The FDA could fulfill its mandate perfectly by rejecting every new drug. Zero unsafe drugs would ever get approved. Mission accomplished. Everyone dies, but safely. You can die from a disease that has a cure sitting in a lab somewhere, but at least you didn't die from an unsafe drug. See the difference? One death is in the FDA's jurisdiction, the other isn't.

60 million people die every year. 2.5 billion people suffer from chronic diseases. A better mandate might be "maximize the average healthy human lifespan." But that's not what you told them to do. You gave them a narrow mandate and they're following it. This is what you call "doing your job" even when your job makes no sense.

The Health Explosion

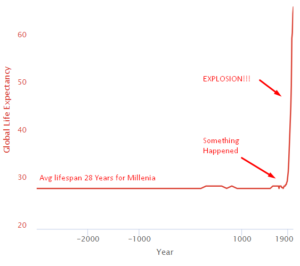

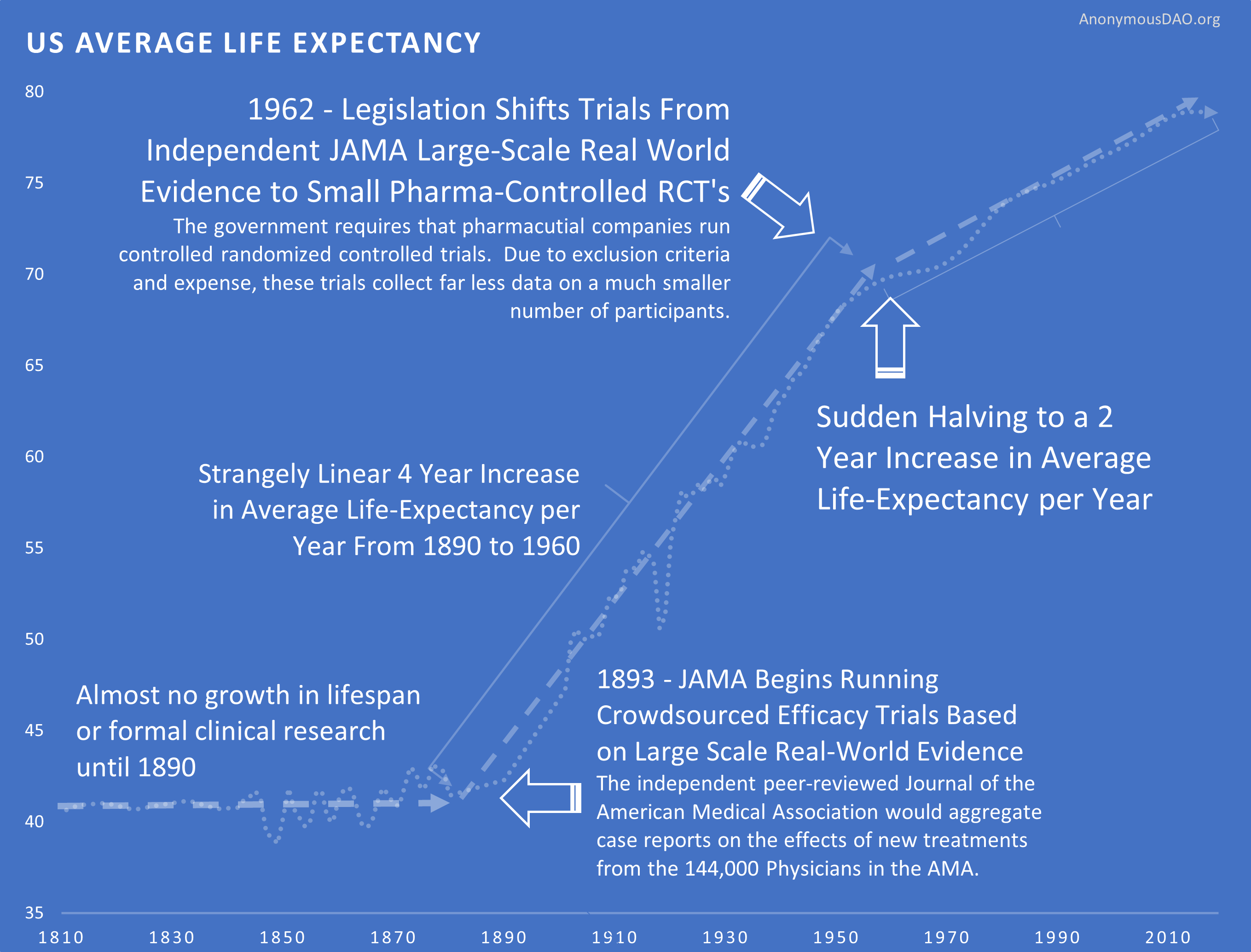

For thousands of years, everything sucked, and you died at 28. Then something happened around 1800, and life expectancy exploded. You went from "probably dead before 30" to "might make it to 80" in about 200 years.

This is the steepest increase in human lifespan in all of recorded history. For context, Cleopatra lived closer in time to the moon landing than to the building of the pyramids. And her life expectancy was basically the same as the pyramid builders. Then suddenly in 1800, something changed. You'll never guess what it was. (It was science and capitalism, working together like a buddy cop movie.)

What Caused the Health Explosion

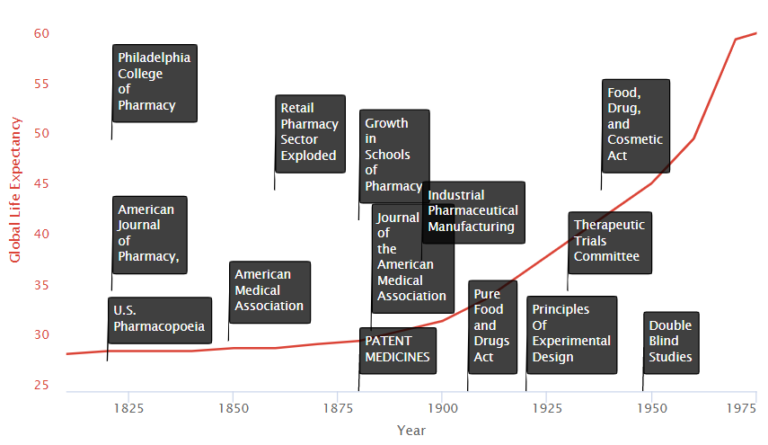

Here's what happened in the centuries leading to this explosion:

We see on the timeline two primary groups of factors:

- Research Improvements

- Incentive Improvements

Research Improvements

Schools of Medicine

An influx of new state-affiliated pharmacy schools in the 1880s and 1890s. The growth in schools of medicine trained physicians and researchers in the systematic collection of clinical data on the safety and efficacy of treatments. They also served as hubs where scientists could share new medical discoveries.

Medical Journals

New medical journals, such as the Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA), began to disseminate discoveries widely.

AMA Drug Certifications

In 1905, the AMA formed its own Council on Pharmacy and Chemistry, which levied a fee on manufacturers to evaluate their drugs for quality (ingredient testing) and safety. Drugs accepted by the Council could carry the AMA’s Seal of Acceptance. The AMA’s Chemical Laboratory tested commercial statements about the composition and purity of drugs in their labs. The Council on Pharmacy and Chemistry followed up with safety

and rudimentary efficacy evaluations designed to eliminate exaggerated or misleading therapeutic claims. Drugs that provided symptomatic relief were awarded the AMA’s Seal of Acceptance.

Cooperative Investigations

During the 1920s, ’30s, and ’40s, medical researchers began to conduct “cooperative investigations.” These were designed to overcome errors attributed to individual observers working in relative isolation and instead replaced them with standardized evaluations of therapeutic research in hundreds of patients.

Freedom to Try

Therapeutic experimentation did not begin to gain a proper foothold in modern medicine until the U.S. legal system stopped equating experimentation with medical malpractice. In 1935, the state of Michigan authorized controlled clinical investigations as a part of medical practice without subjecting the researcher to strict liability (without fault) for any injury, so long as the patient consented to the experiment. In particular, the Court accepted that experimentation was necessary not just to treat the individual but also to help medicine progress. “We recognize,” noted the Court, “that if the general practice of medicine and surgery is to progress, there must be a certain amount of experimentation carried on.”

Incentive Improvements

Medical Patent Protections & Mass Production

In the late nineteenth and early twentieth century, interest in clinical objectivity grew, spurred on by astounding successes in laboratory science and clinical medicine abroad (e.g., the discovery of microbes, pasteurization of milk, development of anthrax and rabies vaccines). International recognition of medical patents contributed to a boom in large-scale industrial pharmaceutical manufacturing led by Bayer and Pfizer. In 1880, patent medicines constituted 28% of marketed drugs; by 1900, however, they represented 72% of drug sales.

The industrial revolution gave way to technologies allowing for mass production and distribution on a global scale. This method was vastly more efficient and profitable than traditional means, and these greater profits drove more significant investment and, thereby, greater medical progress.

The History of Drug Regulation

In the 1800s, snake oil salesmen would make false claims about the concoctions they were selling. The original solution was the AMA Council on Pharmacy and Chemistry certification to ethical drug products that met their standards.

1906 – Ingredient Lists and No Lying on Labels

The 1906 Pure Food and Drugs Act empowered the Bureau of Chemistry (forerunner of the FDA) to seize adulterated and misbranded products. The law also prohibited “false and misleading” statements on product labels. The rule listed eleven so-called “dangerous ingredients,” including opium (and its derivatives) and alcohol which, if present in the product, had to be listed on the drug label. This listing requirement alone inspired many manufacturers to abandon the use of many “dangerous ingredients” following the passage of the 1906 Act.

1938 – Safety Trial Requirements

The Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic (FDC) Act of 1938 is passed by Congress, containing new provisions:

- Extending control to cosmetics and therapeutic devices.

- Requiring new drugs to be shown safe before marketing

Manufacturers were required to demonstrate to FDA that they had carried out all reasonably applicable studies to demonstrate safety and that the drug was “safe for use.”

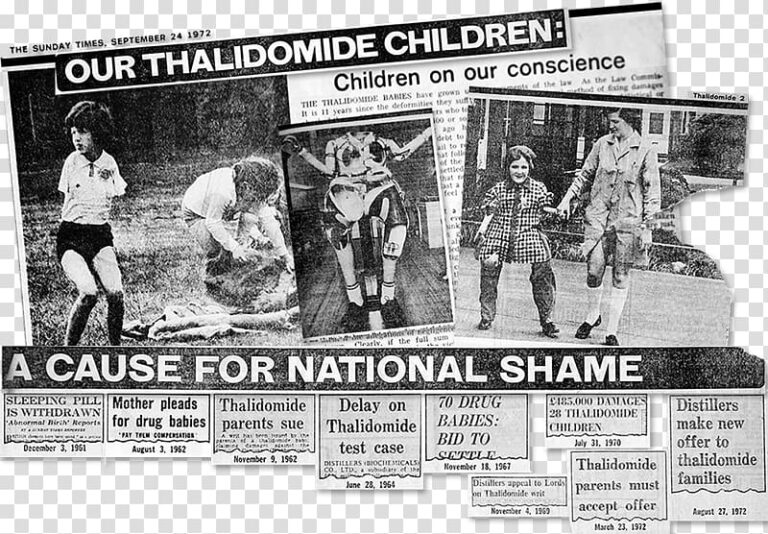

1950's – FDA Protects Americans from the Thalidomide Disaster

In the late 1950s, thalidomide was available in 46 countries to treat morning sickness during pregnancy. Not in the U.S., though. The existing 1938 FDA safety requirements kept it out.

Thousands of children in Europe were born with severe limb malformations. Zero in the U.S. The 1938 safety regulations worked perfectly. This is what you call a "success story" in regulation. The system worked exactly as designed.

But amid terrifying news reports of deformed babies in Europe, the U.S. government felt compelled to "do something." The existing system had completely protected Americans, so naturally, you changed it. This is what you call "solving a problem that didn't happen by creating new problems that will happen." Politics is when you fix things that aren't broken.

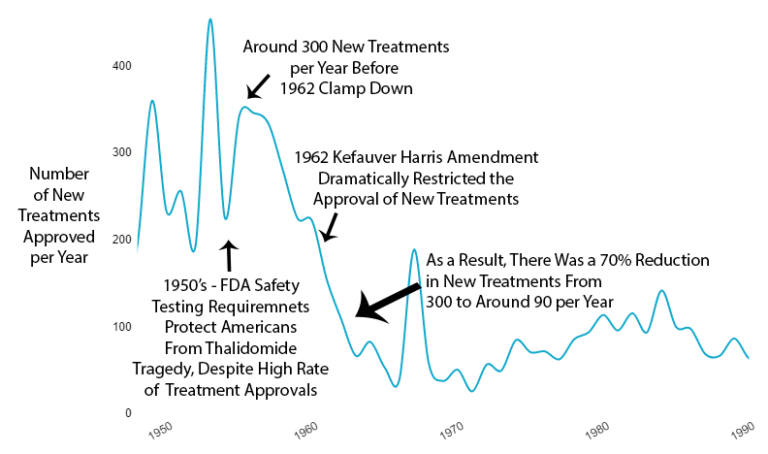

1962 – Kefauver Harris Efficacy Amendment

Safety regulations were already working. So the government added massive new efficacy testing requirements via the 1962 Kefauver Harris Amendment. If it's not broken, add 10 years and $1 billion to the process. This is what you call "improvement" even though everything got worse.

The amendment is called "Kefauver Harris" because it was sponsored by Senator Estes Kefauver and Representative Oren Harris. Naming laws after the people who wrote them is a tradition in government. It makes it easier to know who to blame when everything goes wrong.

Results of Increased Restrictions

Reduction in New Treatments

The new regulations immediately reduced the production of new treatments by 70%. You cut medical progress by two-thirds overnight.

Slowed Growth in Lifespan

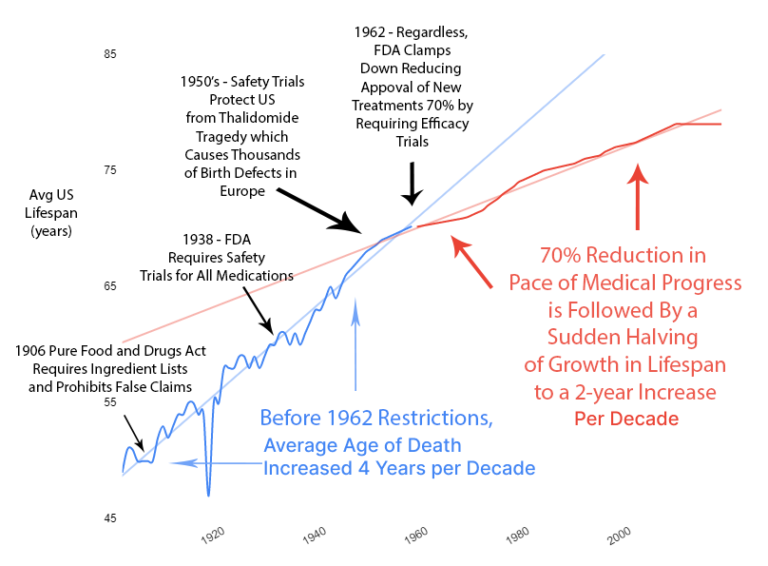

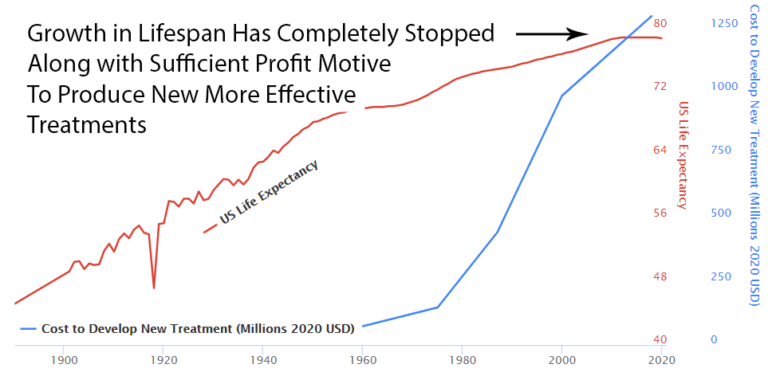

For 50 years before 1962, life expectancy grew by 4 years per decade. A perfectly linear growth rate that had followed millennia of zero growth.

After the 1962 regulations cut medical progress by 70%, life expectancy growth was immediately cut in half. From 4 years per decade to 2 years per decade.

You added regulations. Medical progress was cut by 70%. Lifespan growth was cut by 50%. The timing is notable.

Diminishing Returns?

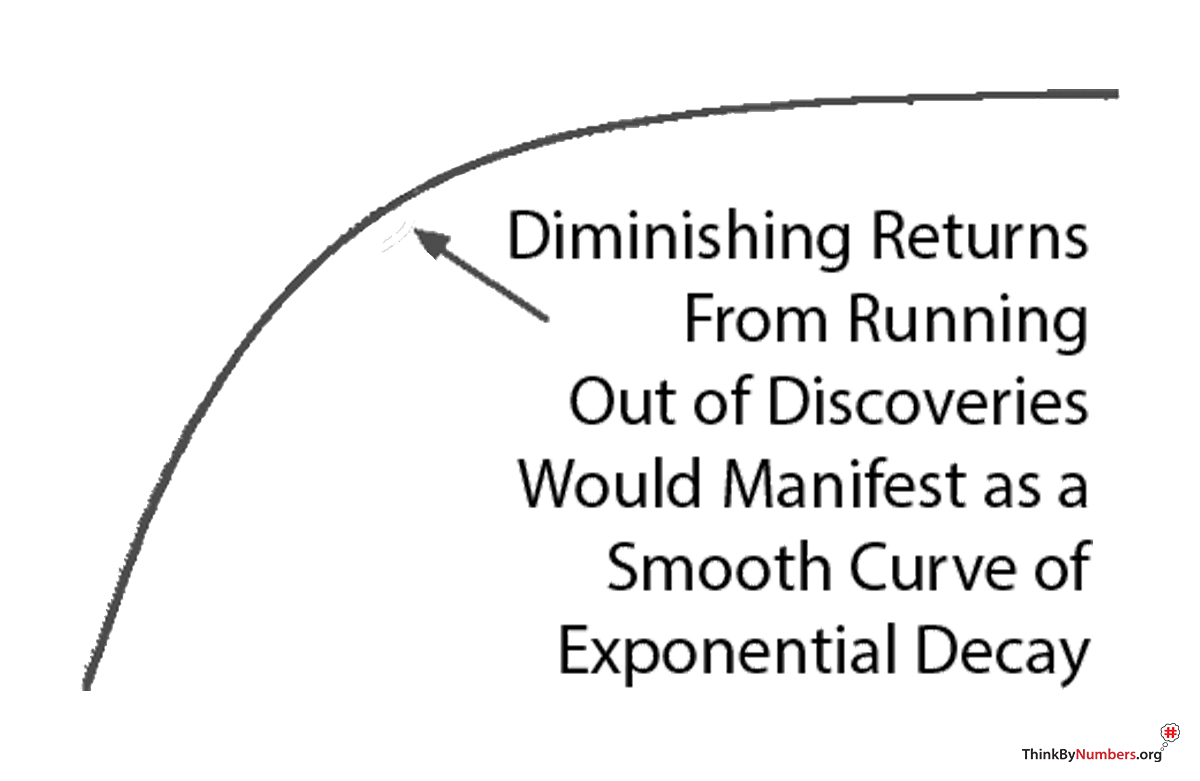

You might say "maybe we're just running out of easy medical discoveries." Diminishing returns are real. But diminishing returns produce exponential decay. A gradual curve downward.

You don't get a sudden, immediate change in a perfectly linear slope. Especially not on the exact year new regulations were implemented.

Also, you're only three lifetimes from George Washington. The modern scientific method has been applied to medicine for 0.0001% of human history. You know almost nothing compared to what will eventually be known about the human body.

You're at the very beginning of thousands of years of systematic discovery. Running out of things to discover is not your problem. Making discovery impossibly slow and expensive is your problem.

2 Year Drug Lag

It takes over 10 years for a life-saving drug to make it through the FDA and become available to dying patients. "Life-saving" and "dying patients" are in the same sentence with "10 years." The irony is not subtle. If you're dying, 10 years might as well be forever. But at least when you die, you'll die knowing the drug that could have saved you was thoroughly tested on other people who didn't die as fast.

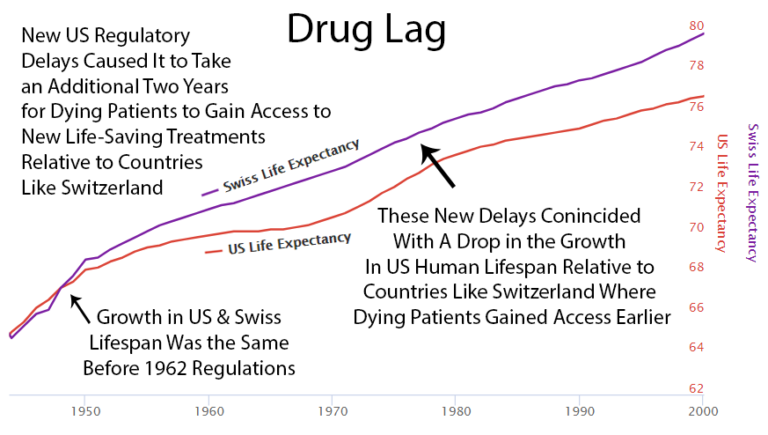

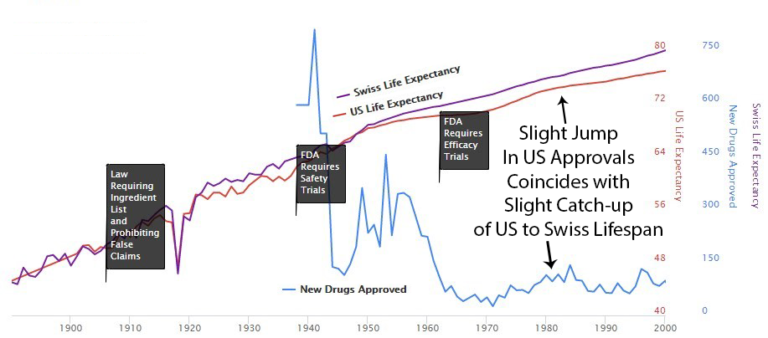

After the 1962 U.S. regulations, life expectancy in the U.S. diverged from Switzerland, which didn't add the same delays.

Possibly a coincidence: U.S. drug approvals increased in the '80s, and the gap with Switzerland got smaller. Then U.S. approvals decreased in the '90s, and the gap expanded again. The correlation is notable.

Here's a news story from the Non-Existent Times by No One Ever, featuring all the people who die from lack of access to treatments that might have existed:

Explosion in Costs

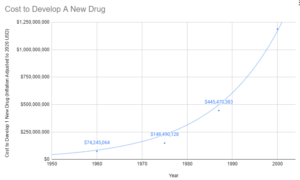

Since 1962, the cost of bringing a new treatment to market went from $74 million to over $1 billion (2020 inflation-adjusted).

You made it 13 times more expensive to save lives. This is what you're doing with mathematics.

Treatments for Rare Diseases Make No Financial Sense

The costs of FDA regulations do not vary with the number of potential patients, so the decline in drug development has been particularly harmful to those suffering from rare diseases. Each rare disease afflicts only a small number of people, but thousands of rare diseases exist. In aggregate, rare diseases afflict millions of Americans: according to an AMA estimate (AMA 1995), as many as 10 percent of the population. Thus, millions of Americans have few or no therapies available to treat their diseases because of increased costs of drug development brought about by stringent FDA “safety and efficacy” requirements. In response to this problem, in 1983, the Orphan Drug Act was passed to provide tax relief and exclusive privileges to firms developing drugs for diseases affecting two hundred thousand or fewer Americans (AMA 1995).

Oligopolies Protect Existing Inferior Treatments

Before 1962, a brilliant scientist could develop a new treatment, raise $74 million for safety and efficacy testing, and bring it to market. With the current cost of getting a new therapy to patients over a billion dollars, there are only a handful of companies with enough money to risk hundreds of millions on a 90% chance of rejection by the FDA. So today, the brilliant scientist goes to one of these companies, and the company buys the patent for several million dollars. It’s likely the drug company already has an existing inferior drug on the market that they’ve already spent a billion dollars getting approved.

Then the drug company has two options:

Option 1: Risk $1 billion on clinical trials

Possibility A: Drug is one of the 90% the FDA rejects. GIVE BANKER A BILLION DOLLARS. DO NOT PASS GO.

Possibility B: Drug turns out to be one of the 10% the FDA approves. Yay!!! Now it’s time to try to recover that billion dollars. However, very few drug companies have enough money to survive this game. So, this company almost certainly already has an inferior drug on the market to treat the same condition. Hence, any profit from this drug will likely be subtracted from revenue from existing, less effective drugs they’ve already spent a billion dollars on.

Option 2: Put the patent on the shelf

Do not take a 90% chance of wasting a billion dollars on failed trials. Do not risk making your already approved cash-cow drugs obsolete.

What’s the benefit of bringing better treatment to market if you lose a billion dollars? Either way, the profit incentive is entirely in favor of just buying better treatments and shelving them.

The current flat line in US lifespan growth and chronic disease burden is completely consistent with a system that completely disincentivizes medical progress.

Efficacy Trials Before 1962

A given drug may be effective at treating hundreds of conditions. However, knowing which conditions a drug may improve is impossible until real-world patients try it.

Before the 1962 regulations, it cost a drug manufacturer an average of $74 million (2020 inflation-adjusted) to develop and test a new drug for safety before bringing it to market. Once the FDA had approved it as safe, efficacy testing was performed by the third-party American Medical Association.

The AMA would collect data from its 144,000 physicians on the efficacy of different drugs for various conditions. Once it was determined which conditions a drug was or was not effective for, the results would be published in the Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA). The AMA would only give its Seal to drugs that it had determined safe and effective for specific conditions.

The 1962 regulations made these large real-world efficacy trials illegal. Ironically, even though the new rules were primarily focused on ensuring that drugs were effective through controlled FDA efficacy trials, they massively reduced the quantity and quality of the efficacy data that was collected for several reasons:

- New Trials Were Much Smaller

- Were Far More Expensive

- Participants Were Less Representative of Actual Patients

- They Were Run by Drug Companies with Conflicts of Interest Instead of the 3rd Party AMA

Exclusion Criteria

Subjects in FDA Trials Are Not Representative of the Actual People Receiving Treatment

External validity is the extent to which the results can be generalized to a population of interest. The population of interest is usually defined as the people the intervention is intended to help.

Phase III clinical trials are designed to exclude most of the population of interest. In other words, the subjects of the drug trials are not representative of the prescribed recipients once said drugs are approved. One investigation found that only 14.5% of patients with major depressive disorder fulfilled eligibility requirements for enrollment in an antidepressant efficacy trial.

As a result, the results of these trials are not necessarily generalizable to patients matching any of these criteria:

- Suffer from multiple mental health conditions (e.g., post-traumatic stress disorder, generalized anxiety disorder, bipolar disorder, etc.)

- Engage in drug or alcohol abuse

- Suffer from mild depression (Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (HAM-D) score below the specified minimum)

- Use other psychotropic medications.

These facts call into question the external validity of standard efficacy trials.

The fact that co-morbidities are excluded also makes it impossible to discover potential new uses for a treatment.

New Trials Were Very Small

Due to exclusion criteria and added costs, patient sample sizes are tiny:

- 275 patients per cardiovascular trial

- 20 patients per cancer trial

- 70 patients per depression trial

- 100 per diabetes trial

You're testing treatments on 20 cancer patients and calling it science. That's fewer people than are in a classroom. You're making life-or-death decisions for millions of people based on data from a sample size that would be rejected in a high school science fair.

Before 1962, the AMA collected data from 144,000 physicians on actual patients. Now you test 20 people in a lab. This is what you call "more rigorous" because the 20 people were very carefully selected. Selection is important when you're trying to make sure your results are not representative of actual patients.

Solution: Collect Data on Actual Patients

In the real world, no patient can be excluded. People with multiple conditions, people on multiple medications, people with drug and alcohol problems - they all need treatment. They all get treatment. But you have no data on how treatments work for them because they're excluded from trials.

Here's how to fix this: collect real-world data from actual patients. Let doctors and patients track what works. Crowdsource the research. The test subjects would be identical to the population of interest. External validity would be perfect.

You had this system before 1962. It worked better. You could try using it again.

The Math: Current Regulations Cause More Deaths Than They Prevent

Studies estimate the FDA prevents 5,000 to 10,000 deaths per decade by keeping dangerous drugs off the market. This is based on pre-FDA deaths in the U.S. and deaths in countries without an FDA. The studies use math to estimate counterfactual scenarios. Counterfactual is what you call something that didn't happen but might have happened if things were different.

Studies also estimate the FDA causes 21,000 to 120,000 deaths per decade through delays in approving life-saving treatments. These are deaths from diseases that could have been treated with drugs that existed but weren't approved yet. The people died waiting for permission.

Here's the math:

- Lives saved: 5,000-10,000 per decade

- Lives lost to delays: 21,000-120,000 per decade

- Net result: 11,000-115,000 additional deaths per decade

The FDA kills 2 to 12 people through delay for every 1 person it saves from a dangerous drug. This is called the "net effect" which is when you add up all the good things and subtract all the bad things and see if you get a positive number or a negative number. In this case, you get a negative number. Negative is bad in the context of human deaths.

This is the net outcome. Lives saved minus lives lost equals more deaths. The math requires third-grade arithmetic. You have third grade, so the confusion is notable. If you're thinking "but surely the experts must know this and have a good reason," the answer is: they do know this, and they do not have a good reason.

Sources

- Google Spreadsheet of FDA Spending vs. Life-Expectancy

- Summary of NDA Approvals & Receipts, 1938 to the present

- Theory, Evidence, and Examples of FDA Harm

- DATA

- GDP

- Reform, Regulation, and Pharmaceuticals — The Kefauver–Harris Amendments at 50

- Consumer Price Index

- Estimates of World GDP, One Million B.C. – Present

- Newspaper Generator

- Report suggests drug-approval rate now just 1-in-10

- How many people die and how many are born each year?

- Gross World Product per capita

- History of Clinical Trials

- How many life-years have new drugs saved?

- CATO

- Medical Innovation

- Timeline History of Clinical Research

- FDA and Clinical Drug Trials: A Short History

- Do Off-Label Drug Practices Argue Against FDA Efficacy Requirements?

- Reform Options

- Before Occupy: How AIDS Activists Seized Control of the FDA in 1988

- A Brief History of the Center for Drug Evaluation and Research

- Milestones in U.S. Food and Drug Law History

Comments