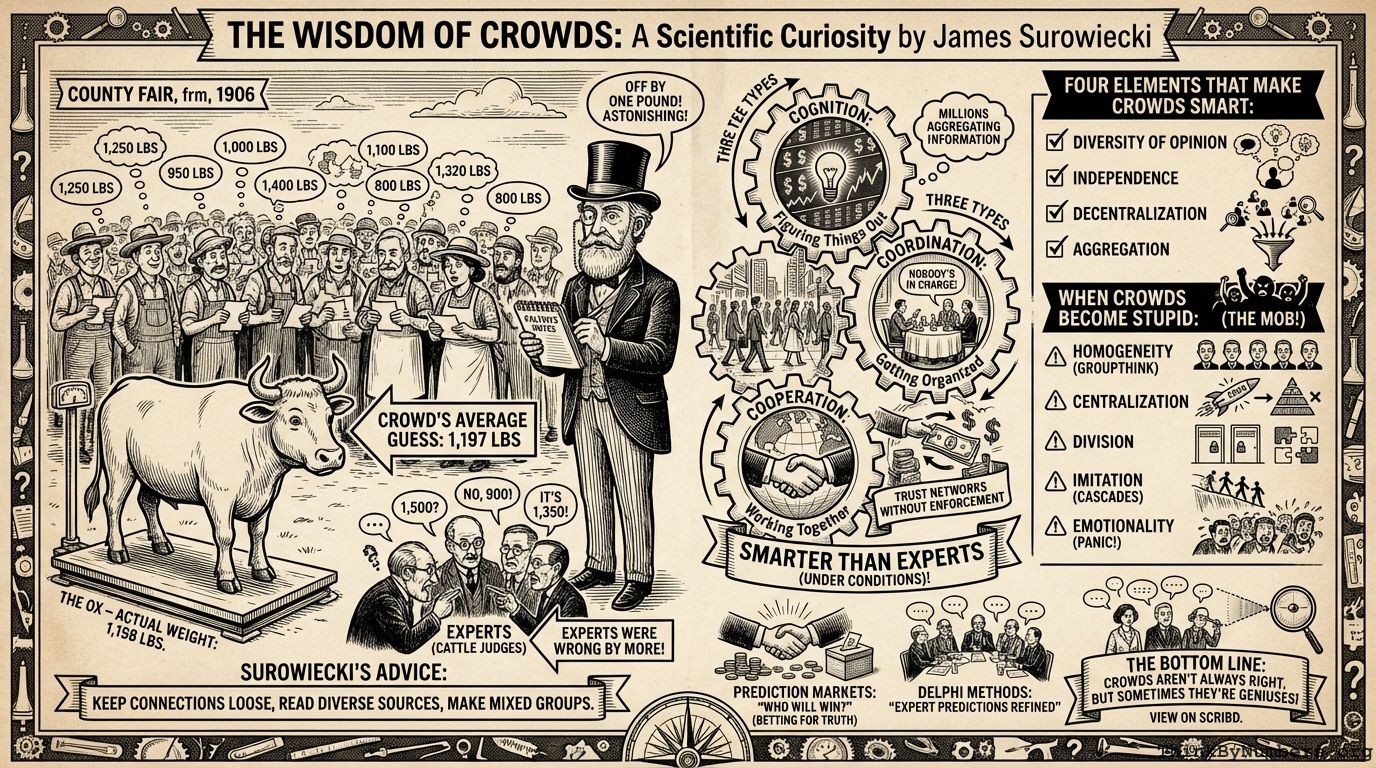

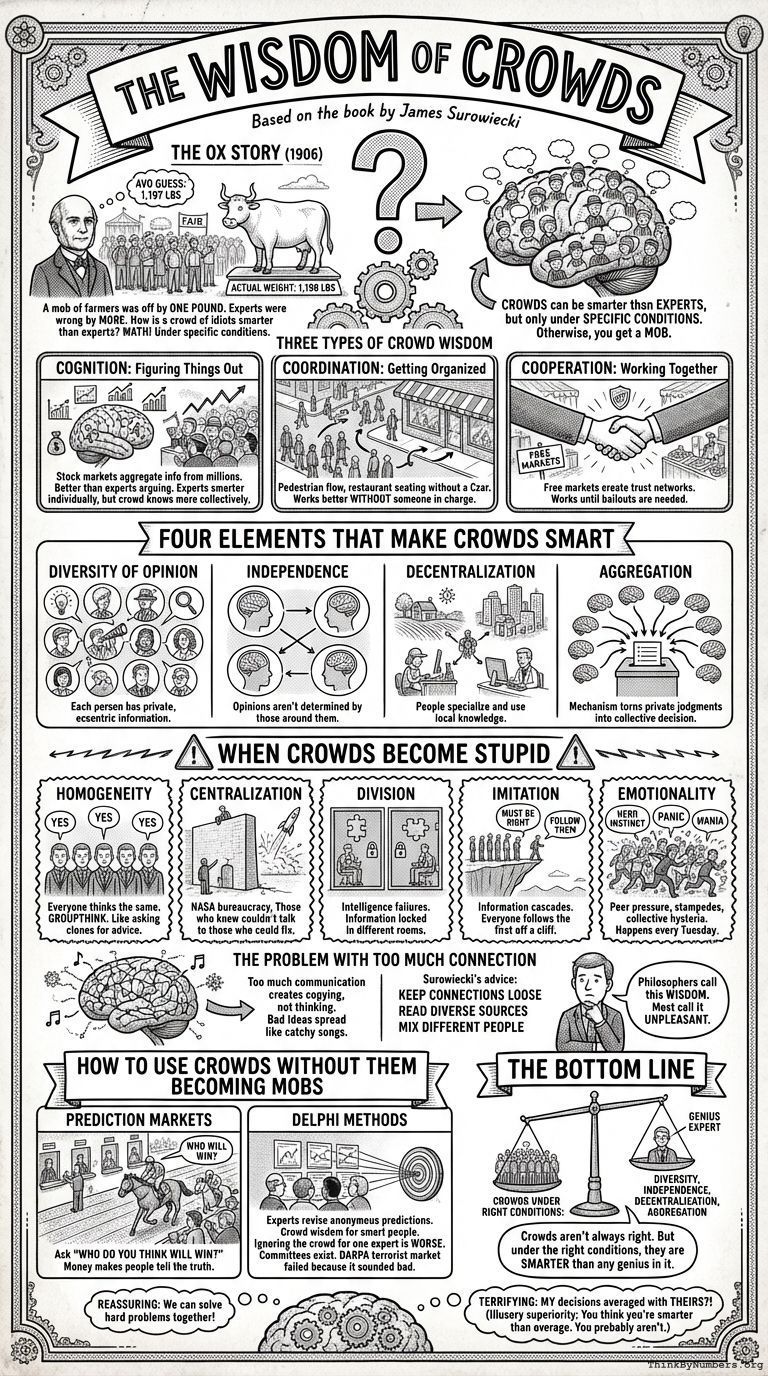

In 1906, Francis Galton went to a county fair and watched people guess the weight of an ox. The average guess was 1,197 pounds. The ox weighed 1,198 pounds. The crowd - a mob of random farmers who'd probably never weighed an ox in their lives - was off by one pound. The cattle experts were wrong by more.

This raises an important question: How is a crowd of idiots smarter than a room full of experts? The answer is math, but in a way that makes philosophy majors nervous.

Turns out a mob of random people can make better decisions than experts, but only under very specific conditions. Otherwise you get a mob, which is generally bad. The conditions matter. This is why democracy sometimes works and sometimes elects people who think the Moon landing was fake.

James Surowiecki wrote a book called The Wisdom of Crowds explaining when crowds are smart and when they're just crowds. There are three types:

Cognition: Figuring things out

- Stock markets aggregate information from millions of people betting real money

- This works better than a committee of experts in a room arguing about what they THINK will happen

- The experts are smarter individually, but the crowd knows more collectively, which doesn't make sense until you do the math

Coordination: Getting things organized without anyone in charge

- Pedestrian traffic flows on sidewalks without a Traffic Czar

- Restaurant crowds distribute themselves across different places without a Dinner Coordinator

- Nobody's in charge, but somehow it works better than if someone WAS in charge

- This is very upsetting to people who like being in charge

Cooperation: Working together without someone forcing you

- Free markets create trust networks without enforcement

- This is supposed to prove something about human nature, but economists disagree on what

- It works until it doesn't, at which point everyone asks for a bailout

Four elements that make crowds smart:

| Criteria | Description |

|---|---|

| Diversity of opinion | Each person has private information, even if it's just an eccentric interpretation. |

| Independence | People's opinions aren't determined by those around them. |

| Decentralization | People can specialize and use local knowledge. |

| Aggregation | Some mechanism exists for turning private judgments into a collective decision. |

When crowds become stupid:

Homogeneity: If everyone thinks the same way, you don't get diverse opinions. You get groupthink. This is like asking five clones of yourself for advice and being surprised when they all agree with you.

Centralization: The Space Shuttle Columbia exploded because NASA's bureaucracy was so hierarchical that low-level engineers who knew about the problem couldn't get anyone important to listen. The people who knew what was wrong weren't allowed to talk to the people who could fix it. This is called "organizational structure" and it kills astronauts.

Division: The Intelligence Community failed to prevent 9/11 partly because one department's information couldn't reach another department. They had all the puzzle pieces, but each piece was locked in a different room and nobody had all the keys. This is called "security" and sometimes it's very secure against your own organization learning things.

Imitation: When people can see what others choose, they stop thinking and start copying. This creates "information cascades," which is the fancy term for "everyone following the first person off a cliff." The first three people make real decisions. Everyone else just follows them because surely that many people can't be wrong. (They can.)

Emotionality: Peer pressure, herd instinct, collective hysteria, stampedes, panics, manias, and crazes. Basically any time someone uses the phrase "everyone's doing it." This happens every Tuesday. Sometimes Wednesday too.

The problem with too much connection:

You need people to interact, but not TOO much. Too much communication makes the group stupider because everyone starts copying each other instead of thinking. It's like how one person humming a song can get stuck in everyone's head. Except instead of a song, it's a bad idea, and instead of your head, it's government policy.

Surowiecki's advice:

- Keep your connections loose (not too many close friends who all think the same)

- Read diverse sources (not just things you agree with)

- Make groups that mix different types of people (hierarchies make stupid decisions)

This is basically telling you to have acquaintances instead of friends and to read things that annoy you. Philosophers call this "wisdom." Most people call it "unpleasant."

How to use crowds without them becoming mobs:

Prediction markets ask "Who do you think will win?" instead of "Who do you want to win?"

The difference matters. If you ask "Who will you vote for?" people lie or say what makes them look good. If you ask "Who will win?" and make them bet money on it, they tell the truth. Turns out money makes people honest in ways that morality doesn't.

Delphi methods collect expert predictions, share them anonymously, then let experts revise based on seeing other experts' reasoning. The range of answers narrows toward the correct answer like a focusing lens. It's crowd wisdom but for smart people, which makes it more respectable at dinner parties.

The principle only works if you actually LET the crowd participate. If you ignore them and just ask the smartest person in the room, you get that person's answer - which is worse than what the crowd would have given you. This is why committees exist and why everyone hates them.

Google, Wikipedia, and "Web 2.0" succeeded partly by letting the crowd contribute. DARPA tried to create a prediction market for terrorist attacks and geopolitical events, but Congress shut it down because betting on terrorism sounded bad. Surowiecki thinks this was a mistake, since prediction markets are more accurate than think tanks, but "think tank" sounds more professional than "bet on terror."

The bottom line:

Crowds aren't always right. But under the right conditions - diversity, independence, decentralization, and aggregation - a crowd is smarter than any genius in it.

This is either:

- Very reassuring (we can solve hard problems together!)

- Very terrifying (MY decisions are being averaged with THOSE people?!)

It depends on which crowds you're in and whether you think you're smarter than average. (You probably think you are. Most people do. This is called "illusory superiority" and it affects 80% of people, which is mathematically impossible but psychologically inevitable.)

Comments