Illustration by The New York Times

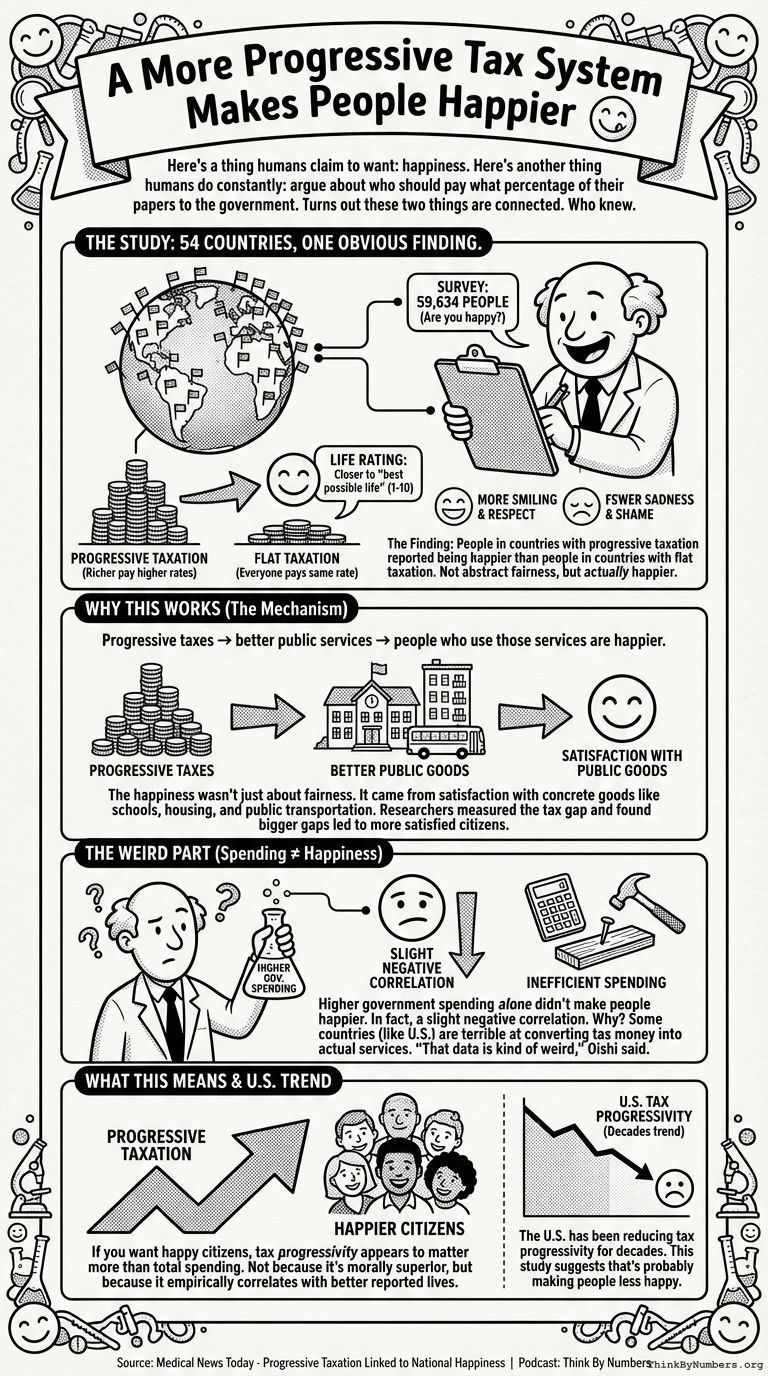

Here's a thing humans claim to want: happiness. Here's another thing humans do constantly: argue about who should pay what percentage of their papers to the government.

Turns out these two things are connected. Who knew.

The Study: 54 Countries, One Obvious Finding

University of Virginia psychologist Shigehiro Oishi and his colleagues did something unusual - they asked 59,634 people in 54 nations if they were happy, then checked what kind of tax system their government used. The results were published in Psychological Science.

The finding: People in countries with progressive taxation (where richer people pay higher rates) reported being happier than people in countries with flat taxation (where everyone pays the same rate).

Not "felt slightly better about abstract concepts of fairness." Actually happier. On a scale of 1 to 10, rating their lives closer to "best possible life." Experiencing more days of smiling and being treated with respect. Fewer days of sadness and shame.

The math here requires third-grade arithmetic, so the decades of debate about this are notable.

Why This Works

The happiness wasn't just people feeling warm and fuzzy about fairness. It came from something concrete: satisfaction with public goods like schools, housing, and public transportation.

Progressive taxes → better public services → people who use those services are happier.

The researchers measured tax progressivity by the gap between the highest and lowest tax rates, accounting for family size and benefits. Then they asked people to rate their life satisfaction and their satisfaction with public services.

Countries with bigger gaps between rich and poor tax rates had happier citizens. The citizens specifically said they were more satisfied with the public goods those taxes funded.

The Weird Part

Higher government spending alone didn't make people happier. In fact, there was a slight negative correlation.

"That data is kind of weird," Oishi said, displaying the scientific term for "what the hell."

His guess: Some countries are terrible at converting tax money into actual services. The U.S., for example, spends more on education and healthcare than most developed countries while ranking poorly in both. It's like using a calculator to hammer nails - expensive and ineffective.

What This Means

If you want happy citizens, tax progressivity appears to matter more than total spending.

Not because progressive taxation is morally superior or ideologically correct. Because it empirically correlates with people reporting that their lives are better.

You can debate economic theory all you want. The people living in these systems have opinions about their own lives, and they shared those opinions with researchers, who counted them.

The U.S. has been reducing tax progressivity for decades. This study suggests that's probably making people less happy, though Americans have many other reasons to be concerned about their choices.

Source

Medical News Today - Progressive Taxation Linked to National Happiness

Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Comments