Every Econ 101 textbook teaches three things:

- Incentives govern behavior

- When something costs more, you get less of it

- Every policy has unseen second-order effects

Most government policies ignore all three. It's like watching someone who passed driver's ed immediately drive into a lake. On purpose. While honking the horn.

Economics is called that because it's all about being economical with the truth.

The Experiment Nobody Wanted

In 2012, NPR's Planet Money created a fake presidential candidate with a platform based entirely on policies economists across the political spectrum agreed on. They assembled a panel including:

- Dean Baker from the Center for Economic and Policy Research (left of center)

- Russ Roberts from George Mason University (self-described "hard core free market guy")

- Katherine Baicker from Harvard (centrist)

- Luigi Zingales from University of Chicago (finance expert)

These economists agreed on policies that should be "no-brainers" for any presidential platform. The platform included eliminating the mortgage interest deduction, ending the employer-provided health insurance deduction, legalizing marijuana, and implementing a carbon tax.

In part 2, Planet Money took this platform to actual voters. The voters hated it. Every single policy. It was like watching someone try to sell vegetables to toddlers, except the toddlers could vote.

One policy that economists particularly love: eliminating the mortgage interest deduction. This deduction costs the government about $70 billion per year and primarily benefits wealthy homeowners. Economists across the spectrum agree it should go. Homeowners across the spectrum agree they will vote against anyone who touches it.

This is democracy.

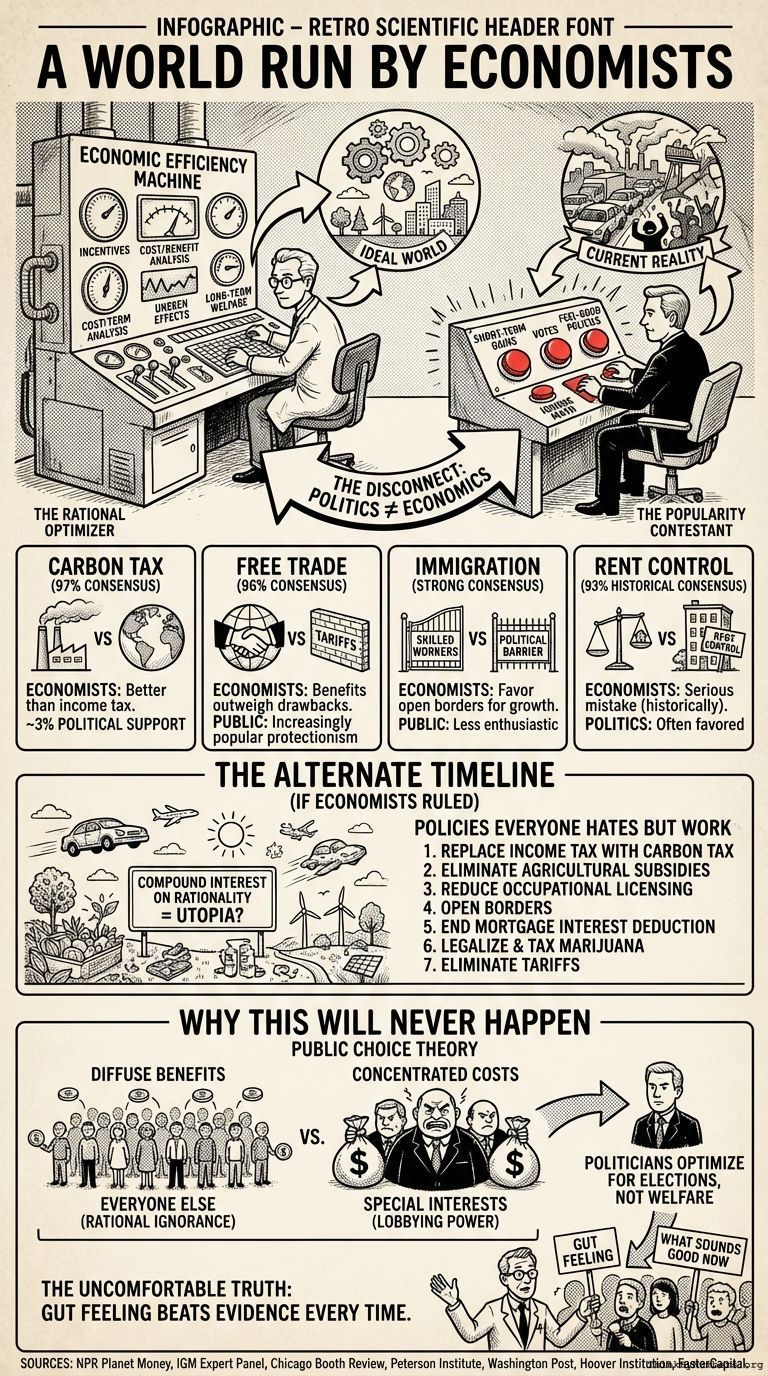

What Economists Actually Agree On

The degree of economist consensus on certain policies is remarkable, especially given that getting economists to agree on anything is traditionally compared to herding cats. Yet on several key issues, the consensus is overwhelming:

Carbon Tax: 97%

97% of polled economists agree that a carbon tax is better than an equal-sized income tax. In a 2012 University of Chicago survey of 40 prominent economists from across the political spectrum, not one—zero, zilch, none—chose the income tax approach over a carbon tax.

In what was perhaps the closest the economics profession has come to consensus, 43 of the world's most eminent economists signed a statement calling for a US carbon tax. This included 27 Nobel laureates, four former Federal Reserve chairs, and nearly every former chair of the Council of Economic Advisers since the 1970s.

The political support for a carbon tax among actual politicians: approximately 3%. Maybe 4% on a good day.

Free Trade: 96%

Over 96% of economists in the IGM Expert Panel agree that the benefits of trade far outweigh the drawbacks. 98% agree US citizens are better off from NAFTA.

Public opinion on tariffs and protectionism: increasingly popular. Using data for 151 countries over 1963–2014, tariff increases are associated with persistent declines in output growth. Trump's first-term tariffs reduced total manufacturing employment by a net 2.7%. Steel tariffs imposed by George W. Bush in 2002-03 were responsible for 168,000 fewer jobs per year in steel-using industries.

When literally 96% of economists say free trade is good and tariffs are bad, continuing to implement tariffs is called "listening to your base" or "economic populism" or "ignoring math."

Immigration: Strong Consensus

Surveys of economists have repeatedly shown that a majority favor more open borders compared to current legal regimes or popular opinion. No group of academic economists favored immigration restrictions in surveyed groups, and only Republican-affiliated economists were neutral.

Public opinion on immigration: considerably less enthusiastic.

Rent Control: 93% (Historical)

A 1990 poll showed 93% of economists thought rent control was a serious mistake. On most major issues like fiscal stimulus, minimum wages, and monetary policy, you can find respected economists on either side. But rent control has historically been an area of strong consensus against.

This consensus is now being challenged by newer empirical research, similar to how minimum wage research evolved. Economic consensus can change when new data arrives. This is called "science." Most policy debates prefer to skip this step.

The Policies Everyone Hates But Work

Here's the disconnect: policies economists agree on are often policies voters and politicians hate. Why? Because economically optimal policies frequently impose visible costs on concentrated groups while providing diffuse benefits to everyone else.

Example: Agricultural Subsidies

Federal subsidies to U.S. businesses cost American taxpayers nearly $100 billion per year. Agricultural subsidies alone represent tens of billions. Economists across the spectrum agree these subsidies distort markets, increase prices for consumers, and primarily benefit large agribusiness corporations.

Farmers in Iowa: love these subsidies. Presidential candidates campaigning in Iowa: also love these subsidies. Economists: hate these subsidies. Guess which group determines policy.

Example: Occupational Licensing

Economists who have examined the market for physician services generally view state licensing as a means to enforce cartel-like restrictions on entry that benefit physicians at the expense of consumers. Similar dynamics apply to hundreds of other occupations that require licenses—from hair braiders to interior decorators to florists.

This raises a profound question: Does society collapse if someone arranges flowers without a government license? Current policy suggests yes. Economists suggest no.

Example: Tax Efficiency

Economist Dale Jorgenson of Harvard University calculated that every additional dollar of taxes collected by the IRS exacts a $1.35 toll on the economy because of collection costs and economic efficiency losses. High marginal tax rates lead to significant welfare loss by discouraging work, saving, and investment.

The economically optimal tax system would be simple, broad-based, and have low marginal rates. The actual tax system is complex, riddled with special deductions, and has high marginal rates on some income while exempting other income entirely.

The mortgage interest deduction alone costs $70 billion per year and primarily benefits high-income homeowners. Economists unanimously agree it should be eliminated. Homeowners unanimously agree economists can get bent.

The Alternate Timeline

If economists had run things for the past 200 years, compound interest on better resource allocation would have given us flying cars by now. Instead, we subsidize corn syrup and ban kidney sales. Humanity has opposable thumbs and invented calculus, but this is what it's doing with those capabilities.

Consider what economists agree on that we're currently not doing:

- Replace income taxes with carbon taxes (better for the economy, better for the environment)

- Eliminate agricultural subsidies (save billions, lower food prices)

- Reduce occupational licensing (increase employment, lower consumer prices)

- Open borders to high-skilled immigration (increase innovation, grow economy)

- End the mortgage interest deduction (save $70 billion, stop subsidizing wealthy homeowners)

- Legalize and tax marijuana (reduce incarceration, generate tax revenue)

- Eliminate tariffs (lower consumer prices, increase efficiency)

Implementing these seven policies would save hundreds of billions of dollars annually, increase economic growth, reduce incarceration, improve the environment, and make most Americans better off.

Political viability: approximately zero.

Why This Will Never Happen

The problem is that economically optimal policies are often politically toxic. Economics optimizes for total welfare. Politics optimizes for winning elections. These are not the same optimization function.

A carbon tax might reduce emissions and improve total welfare, but it raises visible energy prices. Free trade might increase total economic welfare, but it eliminates specific jobs in specific towns. Eliminating agricultural subsidies might benefit 330 million Americans as consumers, but it angers a few hundred thousand farmers who live in swing states.

When the benefits are diffuse and the costs are concentrated, the concentrated interests win. This is called "rational ignorance" and "public choice theory" and "why we can't have nice things."

Sometimes the reason we don't have a perfectly efficient economy is because that would require humans to be perfectly rational. Humans are just tall monkeys who figured out credit cards and then used them to buy things they don't need with money they don't have to impress people they don't like.

The Uncomfortable Truth

Planet Money's economist candidate represented what policy would look like if evidence and consensus actually mattered. The voters' rejection of every single policy represented what happens when you ask voters to choose between "what experts say will make everyone better off in aggregate" versus "what sounds good to me personally right now."

In a contest between expert consensus and gut feeling, gut feeling wins every time. It's democracy's greatest strength and most serious flaw.

When 97% of economists agree on something, and then politicians do the opposite, that's not a difference of opinion. That's choosing to ignore evidence because evidence is unpopular. When doing the economically optimal thing loses elections, and doing the economically destructive thing wins elections, the economically destructive thing becomes policy.

The data showing what works exists. The economist consensus on many policies is overwhelming. Using this information to create better policy is optional but strongly discouraged by electoral politics.

If you ever feel powerless, remember that 43 of the world's most eminent economists—including 27 Nobel laureates—can all agree on a policy, and politicians will still ignore them because it polls poorly in Ohio.

Sources

- NPR Planet Money: The No-Brainer Economic Platform

- NPR Planet Money: Our Fake Candidate Meets The People

- Six Policies Economists Love (And Politicians Hate)

- Economists Sign Statement Supporting Carbon Tax

- The Tax That Could Save the World - Chicago Booth Review

- IGM Expert Panel Surveys on Free Trade

- What Populists Don't Understand About Tariffs - Peterson Institute

- Are Tariffs Bad for Growth? Five Decades of Data - PMC

- Economists Agree: Trump Is Wrong on Tariffs - The Century Foundation

- Economist Consensus on Immigration - Open Borders

- 81% of Economists Agree Rent Controls Are Bad Policy

- The One Issue Every Economist Can Agree Is Bad: Rent Control - Washington Post

- Welfare for the Well-Off: How Business Subsidies Fleece Taxpayers - Hoover Institution

- Subsidies and Welfare Loss - FasterCapital

Comments